Two weekends ago, I had the opportunity to attend a Kenyan wedding. The bibi harusi “bride” was my host mother’s niece, and I was thus able to enjoy a very involved view of the festivities.

Weddings in Kenya are a huge deal. Everyone’s invited – and that means everyone – even passersby are welcome to walk into festivities. The wedding spanned two days – on Friday, the family of the bibi harusi held a traditional Giryama wedding in the family’s homestead in Mariakani. The following day, everyone from the bridal party traveled to a town just north of Mombasa for the Catholic service.

The Giryama Tradition

Inland an hour from Mombasa lies the industrial town of Mariakani, home to the Giryama tribe of the Mijikenda (literally “nine villages”) peoples. A sizable proportion of Mariakani’s residents are employed full-time by local sheet metal and dairy factories, but many still keep livestock and operate small farms. My host mother grew up on a large homestead, with many siblings (I asked my host brother how many aunts and uncles he had – he just laughed). Today, the land has been divided up amongst those children who remain in Mariakani, with each nuclear family having a separate house. However, it is still considered one homestead, and the large extended family still acts as one.

At in the morning, my host brother James and I departed Mombasa for the bridal ceremony. My host mother had left the previous midday in order to prepare for the wedding, and did not want to burden me with sleeping on the ground without a mosquito net as she would have to. The buses in Kenya were in the middle of a minor strike, and so it took quite a bit of waiting around and haggling to get transportation to the rural village. Nevertheless, we arrived in Mariakani little more than an hour after leaving home.

Cutting through shrubbery to enter the homestead, I was greeted by several young adults. They would come to be the first of an incomprehensible count of James’s cousins. Cutting through yet another bush, I witnessed a familiar scene: atop a white-linen-covered dais sat two opulent chairs, facing a long red carpet stretching half the length of the homestead. In every direction were set up rows upon rows of folding chairs, underneath collapsible tents to guard against the beating equatorial Sun. James brought me into the childhood home of the bibi harusi, where I was served tea and a small breakfast.

Once satiated, I was taken out to an open field behind the housing complex. Here too, plastic chairs littered the view, everyone sitting in the shade of the trees overhead. Several hens wandered throughout the grass, pecking at sticks to find food for their loyally-following chicks. I was given a seat alongside two more of James’s cousins and two of his uncles.

Not long afterward, the great event of the Giryama wedding ritual began – the arrival of the groom’s family. The party handed to my host mother a suitcase allegedly containing the bridal gown (today, the suitcase is empty as the bibi harusi has long beforehand picked out her dress) which she then carried above her head. The vibrantly-dressed women of the groom’s party surrounded my host mother, and the group marched towards the bride’s home. There, the brothers of the bibi harusi had deadbolted the door and demanded payment of $50 in order for the groom to take away their sister. Thus ensued a call-and-response shout between the bride’s male relatives and the groom’s female relatives, with my host mom standing right in the middle, sweating profusely from carrying the suitcase. After around twenty minutes, a deal was struck and the door was opened. The two families met indoors for the next few hours, preparing the rest of the wedding.

It quickly became apparent that more seating and serving dishes would be necessary to provide for the rapidly growing wedding attendees, and so I was whisked away to retrieve chairs from a neighbor. About three hundred feet down a dirt road was a small home with a yard containing a few banana trees and a roaming housecat. As I entered, a dozen children marched out of the front gate with chairs above their heads. I scooped up a few for myself and followed the gnome-like inverted chairs back to the celebration.

With everyone seated, it was time for the formalities. The groom and best man sat in two chairs, each wearing a red fez. Two chairs sat empty until two women, cloaked in kanga, were led out of the bride’s home and sat beside the groom. A sequence of elders – including my host mother – gave speeches to the four seated people in Swahili, of which I understood almost nothing. An older man held aloft a skewered coconut, split in half and filled with water, and had a small drink. He then spat the water behind the shoulders of each seated person, as blessings. Upon receiving all the necessary blessings, the groom was tasked with identifying which of the hooded figures was his bibi harusi and which was her bridesmaid. I never got to see the result, but I know if he had chosen wrongly he would have had to pay a sizable fine to the bride’s family.

Soon after bringing chairs over to the wedding, it was time to begin serving the food. All at once, the young men surrounding me stood up and converged behind the house. In a large enclosure were five enormous sufuria “cooking vessels”, with a large team of professional cooks hard at work. The day beforehand, two cows were slaughtered and were tossed into the vats in their entirety, allowed to slow-cook overnight for a mouthwatering tenderness. With the efficiency of an assembly line, large two-foot-wide serving dishes were filled with golden rice and topped with a heap of beef and just a little bit of vegetables. People ran back and forth to lay out one hundred of these dishes in a grid on the ground, while the young men stood around like vultures. Once the mat was completely full, I expected everyone to grab one for himself and devour the biryani ravenously; however, the actual procedure was quite a surprise. One man yelled “go, go, go!” and the surrounding crowd descended upon the plates. Each man picked up not one but two serving dishes, and ran out towards the back hedge. An unfamiliar voice instructed me to “grab two and follow me,” which I complied with. Rather than eating first, the young men have the role of delivering the plates of food to everyone at the wedding. Each serving dish can feed three to five people, and so when I carried my red-hot metal dishes out to the back of the homestead, I found hundreds of children sitting cross-legged awaiting their delicious meals. Setting down the first biryani, I felt relieved from the excruciating pain of the hot metal dish. But I soon realized it wasn’t even close to the end. My host brother waved me back to the outdoor kitchen, where there were just as many dishes as there had been when I left. We hadn’t even fed all the children, and there was still most of two cows stewing. I buckled in and braced my hands for what became a half hour of running all across the homestead with red-hot metal in hand. Everyone was having fun carrying the plates, and it was quite exciting. I still don’t know, however, how nobody else seemed to be treating their hands as if on fire.

Eventually, the food was dispersed. By the time we were finished serving, most of the children had eaten and sent their plates back to be washed. Yet another cousin of my host family’s ushered me into a dark hallway, where he and two others had stowed away two full plates of biryani. After rinsing our hands, we dug in. Many foods in Kenya are eaten with the hands, and this was no exception. I would scoop up rice, pull a strip or two off the hunk of tender beef, and maybe get a little of the hot chili before forcing the formless mass down my gullet. Squatting above a cement floor with very little lighting, hands covered in rice and sauce, I ate without a doubt the best meal I’ve had in Kenya.

With everyone full and excited, the friends of the couple gave brief speeches on the red carpet before the children’s favorite event: the cake-cutting. The bride stood up out of her seat and walked agonizingly slowly toward the three-level wedding cake. As I watched, I realized the top two levels were cardboard and the actual cake was much smaller than expected. The children certainly noticed as well, as I believe they inherently knew this would come down to a free-for-all to get a morsel of the sugary dessert. Sure enough, the kids had to be corralled into a line to get their one cubic inch of cake, and those in the back of the line came out quite unlucky.

The live band struck a faster tune, and everyone went out into the central area to dance to the music. At one point, there was nothing but a solid mass of color as far as the eye could see. Everyone was quite jolly from both the food and the ample supply of palm wine, a bizarre (and strikingly strong) alcoholic drink made purely from the raw sap of a palm tree left to sit for 24 hours. Sadly, the band had to leave by sundown, as the county government had a week beforehand outlawed live music at nighttime in order to curb teen pregnancy.

In the evening, my host sisters arrived after a long day at work, and prepared for their roles at the following day’s ceremony. Long after the sun had set, James and I departed to return home to Mombasa for the night.

A Catholic Rite

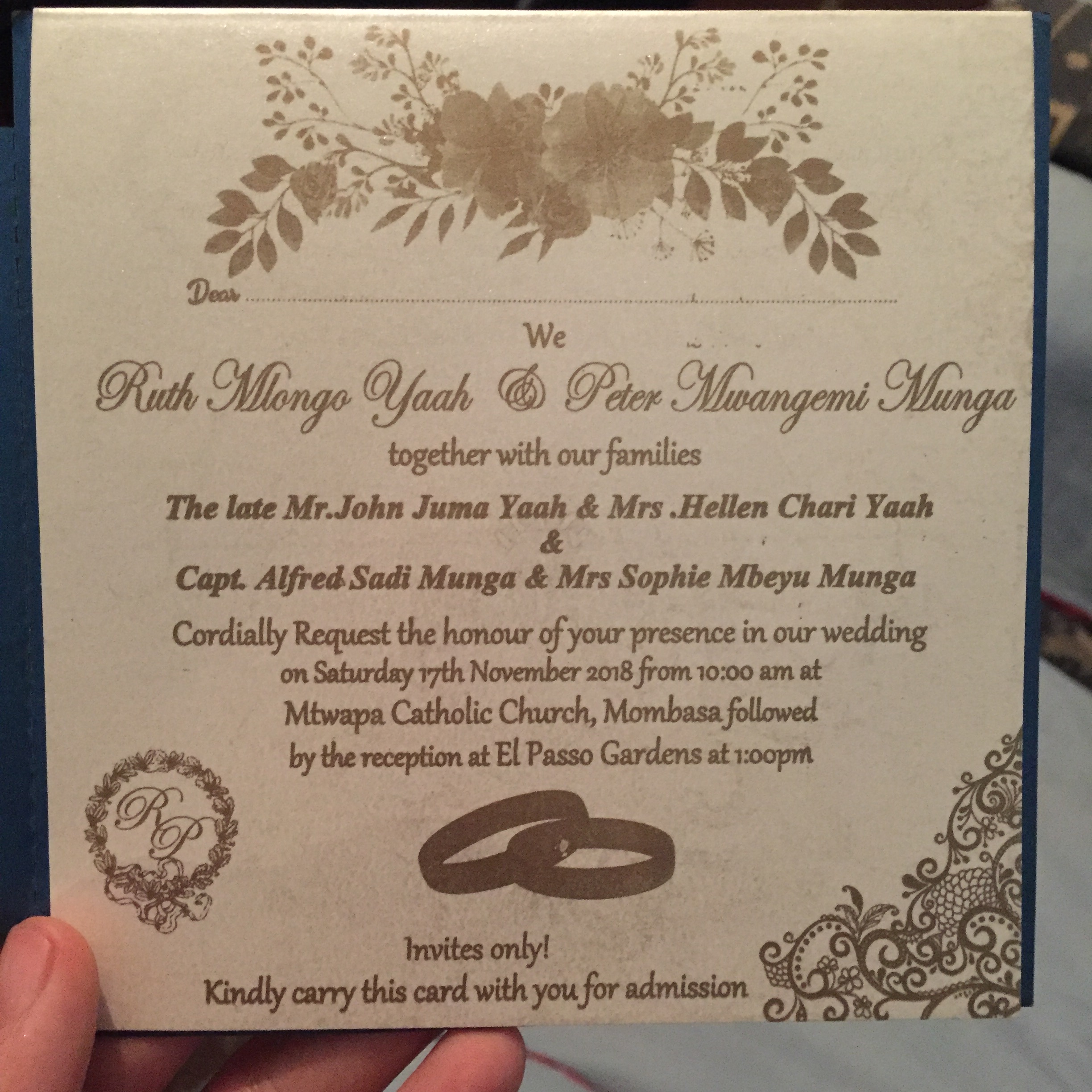

On Saturday, James and I again woke up early to attend the Catholic wedding service. This one was held in the town of Mtwapa, north of Mombasa and coincidentally where my classmate Alyssa resides. The directions weren’t exactly clear on the exact location, so my plus-one ended up arriving long before I did.

Having staked out nice seats directly under a ceiling fan, Alyssa and I watched as the bridesmaids and groomsmen walked down the red carpet. Incomprehensibly, each of the seven pairs of people walked the length of the church stepping forward only an inch at a time, to some blaring pop song which the audio team couldn’t keep at a consistent volume.

If you’ve ever been bored at an arduous religious service, try a Catholic wedding performed exclusively in a foreign language. I had no idea what was going on for the vast majority of the service. It was even hard to see the altar, as there was a team of cameramen across the red carpet loudly taking photos and even flying a video camera drone inside the church. Kenyans love weddings so much that they have a television show every Sunday displaying a different East African wedding, and this one was (un)lucky enough to be selected. The acoustics in the building were horrendous, so all I heard were camera shutters and the whirring of the drone. Nevertheless, I can’t exactly complain as I wouldn’t have understood the priest if I could have heard him. Only when the priest presented those odd Catholic wafers did I realize the service was wrapping up, and flowed out with the rest of the attendees.

This particular wedding was unusual in that the reception was to be funded entirely by the family of the bwana harusi, who are more reserved than the family of the bride. Since they were footing the bill entirely, they decided to cap the reception at four hundred attendees. When I first heard this, I thought it was a reasonable cap – after all, I don’t know 400 people I’d invite to my own wedding; however, it has not gone over well amongst friends & family, many of whom apparently feel very much excluded.

The reception was held at a quiet outdoor arboretum, with dozens of numbered round tables. Alyssa and I were directed to one of the first, and thus were relieved to be called first to go to the buffet. There was a large sampling of Kenyan meats there, and I ate so much I felt in pain for quite some time afterward. Even still, it did not compare to the village biryani.

Following some more speeches by friends and family, a second cake-cutting ritual commenced, this time with each attendee able to get at least one ration of a cubic inch of cake. As I turned to look around, I realized everyone had deserted the reception as soon as they got cake. I was very confused, as the sun was still high in the sky – the wedding couldn’t be over yet; after all, the celebration in Mariakani went from dawn to late at night. I checked with my host mother, who confirmed my suspicions. There was no dancing, no partying, just a rushed meal and then dispersal.

In all, it was a spectacular experience and I hope I get the chance to attend a Kenyan wedding again in the future. I just wish I could have shown Alyssa the real party in Mariakani instead of the subdued church-service-and-meal I invited her to. Maybe next time. ❧